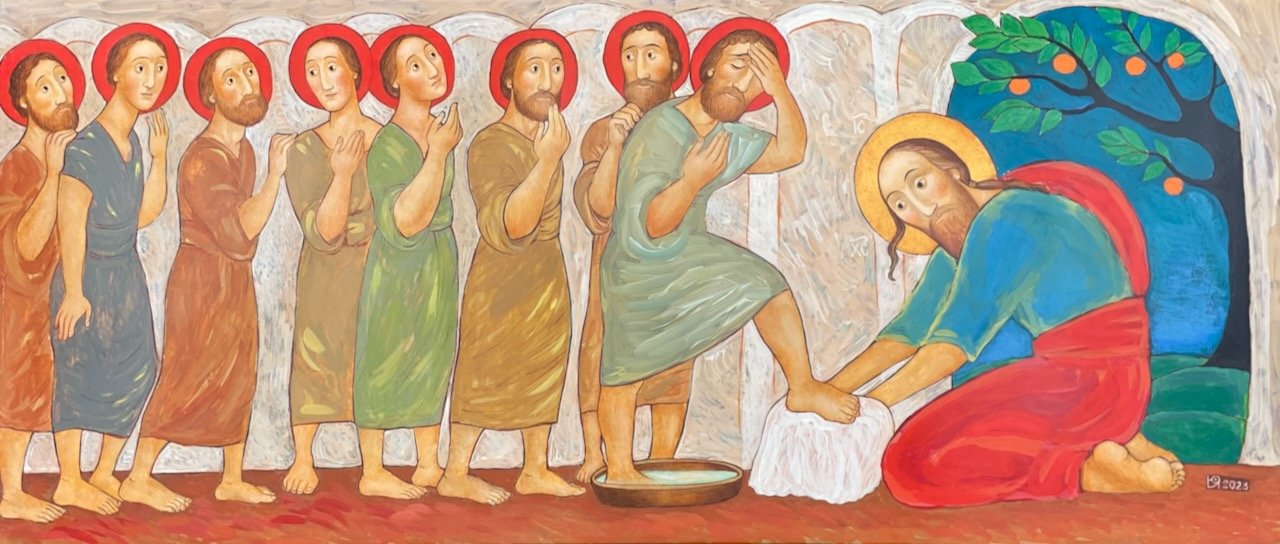

The Washing of the Disciples’ Feet

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

28” x 12”

Inquire about Price

The Transfiguration

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

(Jesus is in the center, flanked by Elijah and Moses, with the Apostles Peter, James and John below)

15 1/2” x 19 3/4”

Sold

Julia Stankova

Our good friend Julia Stankova's works nearly bring us to tears each time we visit her in her apartment in Sofia, Bulgaria. Their aesthetic beauty captures our hearts in a way no other artistic creations do, moving our spirits to revel in their beauty.

Julia was born in 1954 in Haskovo, Bulgaria, and raised in Sofia. At the age of 13, she began taking private lessons in drawing and painting in order to apply to the National Academy of Fine Arts six years later.

Due to the political situation in Bulgaria at the time, she was not given a chance to follow this path, and had to become a mining engineer instead (MA, Mining and Geology University, Sofia, 1978), practicing in this capacity for 12 years. Despite this, she never abandoned her idea of becoming an artist and when the democratic changes happened (1989), she could at last return to her real interest.

Her first step in this direction was to start working in a private restoration studio run by friends. There she had the opportunity to closely observe and touch Bulgarian icons from the 18th and 19th centuries. The purity of feeling radiating from these icons inspired her to start studying the biblical texts and the philosophical principles of the Byzantine pictorial system. Her interest in this subject led her to study theology (MA, Sofia University, 2000).

Later, when she left the restoration studio, she was already mastering the technique of icon-painting on wooden surfaces. She started to develop a kind of symbolic art supported by her knowledge of the Byzantine pictorial heritage, on the one hand, and her emotional attraction to the biblical texts, on the other.

Art scholar Ivan Dodovski said of her works: "I am convinced that the icons of Julia Stankova will inspire real debates, because -- as every great art -- they are apparent and fundamental provocation. They are not works-copies, made in the shadow of the museum-determined Byzantine icon painting; entirely following its canonical-dogmatic principles. These works are the witness of the freedom of creation. They are also proof, peculiar remembrance, that the artistic language of Byzantium is not a metaphor or lamenting for the lost, but a trans-historical perspective."

Saint Francis of Assisi

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

9 3/4” x 20”

Inquire about Price

Guardian of the World

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

8” x 10”

Sold

Madonna and Child

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

5 3/4” x 8”

Inquire about Price

Parting

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

12" x 6"

Sold

Theotokos (Mother of God) II

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

6” x 8”

Sold

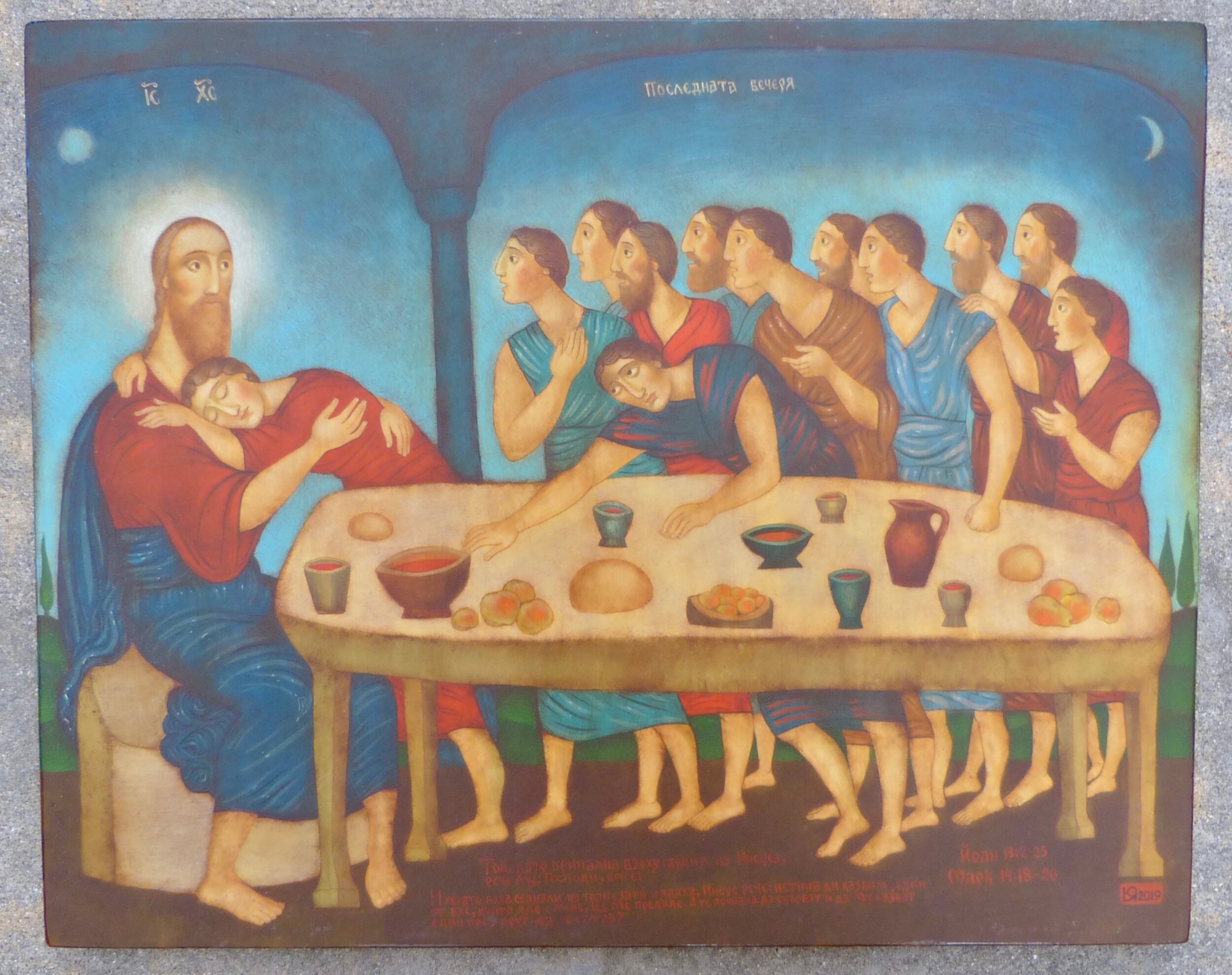

The Last Supper

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

15 1/2” x 19 3/4”

Sold

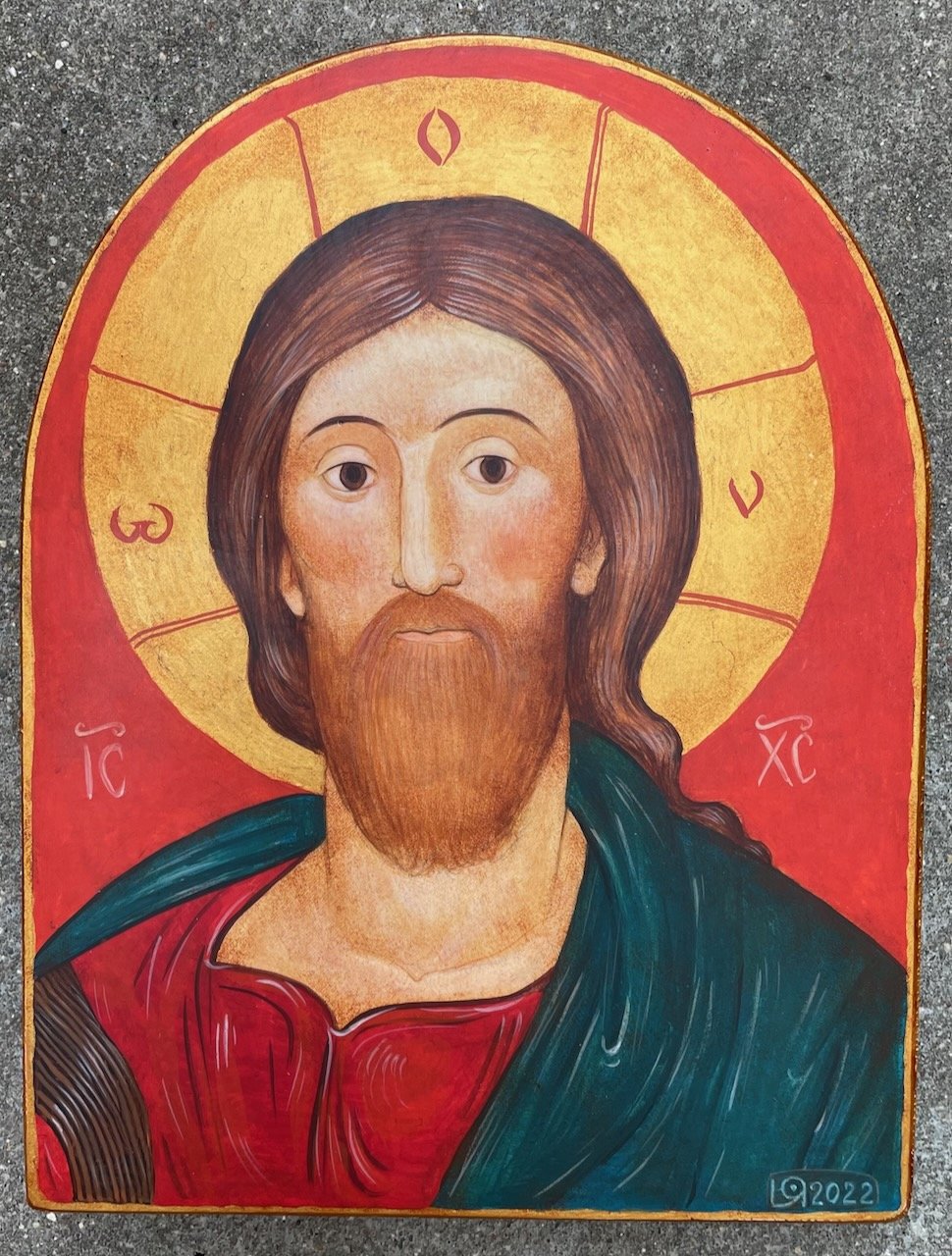

Christos Pantocrator

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

6” x 8”

Sold

Noah’s Ark

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

12” x 16”

Sold

Heavenly Wanderer

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

7” x 9”

Sold

Found Sheep II

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

12” x 16”

Sold

The Entry into Jerusalem

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

14" x 10"

Sold

The Annunciation

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

8" x 10"

Sold

The Resurrection of Lazarus

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

13” x 19”

Sold

The Healing of the Blind Man of Bethsaida

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

12” x 16”

Sold

Jesus Pantocrator

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

7 1/2" x 11"

Sold

Madonna and Child

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

6" x 8"

Sold

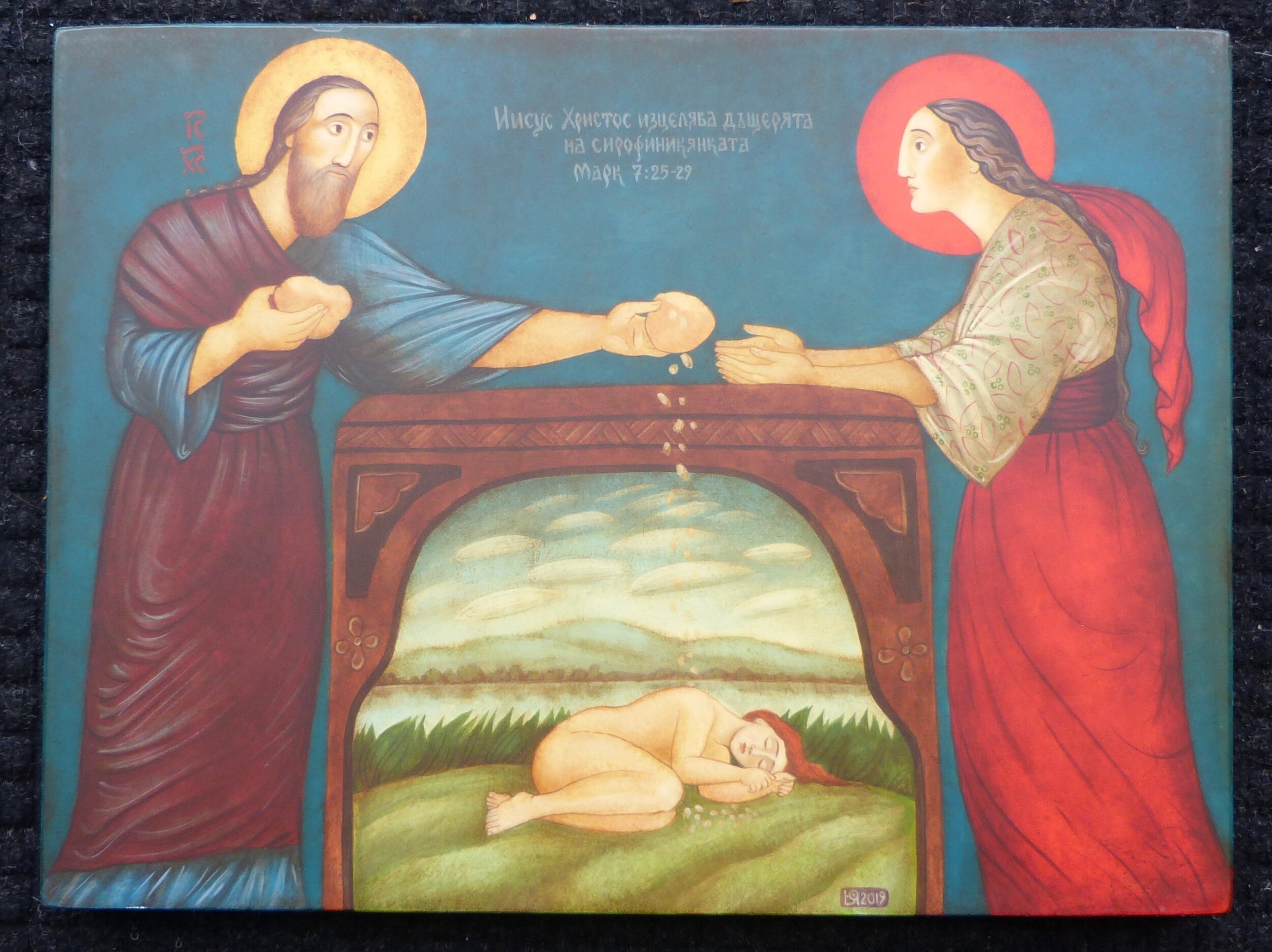

The Faith of a Syrophoenician Woman

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

16” x 12”

Sold

Found Sheep I

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

16” x 20”

Sold

The Anointing of Christ

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

16” x 20”

Sold

The Last Supper

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

19 1/2” x 12”

Inquire about Price

St. George and the Dragon

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

7 1/2” x 10 1/2”

Inquire about Price

The Boat Church

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

19 3/4” x 15 1/2”

Inquire about Price

Body, Spirit and Soul

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

19 3/4” x 15 1/2”

Inquire about Price

Creation of Adam

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

10” x 14”

Inquire about Price

The Guests of Abraham and Sarah

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

19 1/2” x 14”

Inquire about Price

Acts of Eliaz

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Based on I Kings 19:4-5. Eliaz (Elijah) has been faithfully responding to God’s calling, but continues to be humiliated by others, so he rests under a broom tree, depressed, and an angel of God comes to comfort him.

19 1/2” x 11 3/4”

Inquire about Price

The Old Testament Trinity

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

16" x 11 1/2"

Inquire about Price

Annunciation

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Vintage (1990)

10” x 13”

Inquire about Price

Theotokos (Mother of God) I

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

8” x 12”

Sold

The Healing of the Blind-Born Man

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

15 1/2” x 19 3/4”

Sold

Found Sheep III

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

12” x 16”

Sold

Noah’s Ark

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

12” x 19 3/4”

Sold

Christ and the Samaritan Woman

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

16” x 12”

Sold

Jonah

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

Sofia, Bulgaria

11 1/2” x 16”

Sold

The Conception of Anna

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

12” x 16”

Sold

Healing of a Demon-Possessed Man

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

12” x 16”

Sold

Last Supper

By Iconographer and Fine Artist Julia Stankova

19 1/2” x 15 1/2”

Sold